The Beginning for Lecture Theatres

The origins of the ‘lecture’, Latin for ‘reader’, came from exactly that; simply reading a set text. The 10-century continuation of the traditional lecture can be explained through its lengthy cultural and educational history that has been honoured, all while methods of teaching and technology have been able to advance with it. Robert Beichner provides an excellent account of the history of lecture halls. It’s earliest purpose was surrounding religious teaching, as Church Dogma required its large clergy to be educated. As it was found that this larger group were generally good at copying spoken words down and had the remarkable ability to produce written copies of scriptures accurately. Hence, why the church’s Pope Gregory VII decided that these skills could be utilised in a beneficial way by allowing them to copy a religious manuscript read by a ‘lecturer’. This would be done in a lecture hall, where the lecturer leading the session was legally unable to deviate from the written text, as they could have consequently faced a fine. By copying the lecture word-for-word, the information provided could be passed on and lectured by the audience in a continuous chain effect.

Gradual Changes to the Lecture Model

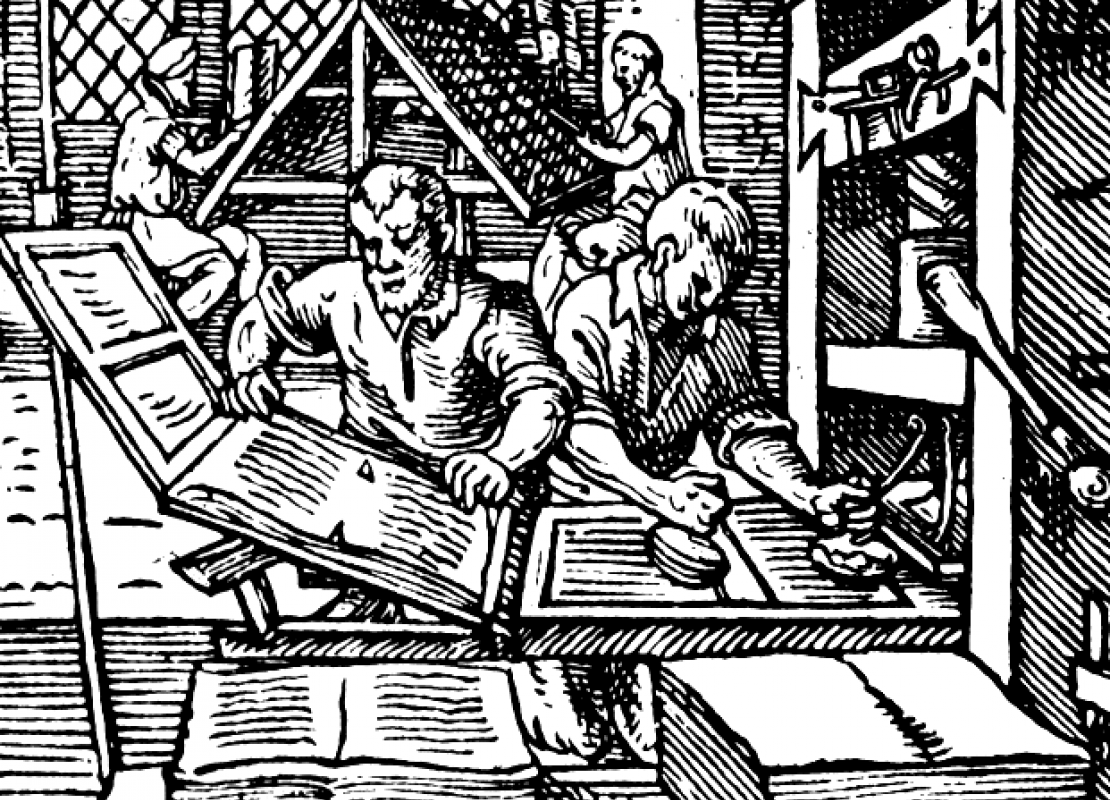

Over time, as communities were becoming more familiar and aware of the lecture as a primary teaching method in universities, along came the novelty of the printing press, which saw the increase in accessible books and written resources that were lacking prior to this point. This leads us to questioning the need for lectures when research could have been carried out through one’s own reading. The answer surrounds the sense of authority that has always been asserted by lecturers in higher hierarchy than the students.

Despite its past success, it has been realised in modern times that university students were no longer learning as much effectively from lectures alone. The early 1800’s saw the introduction of laboratory teaching, as a more active form of learning, as opposed to the passive listening process of the lecture. Physicist Robert Millikan began advocating this teaching method and its importance in providing students with a more practical experience involving the process of learning by doing.

With the movement towards more active learning came the development of new educational technologies. The student response system, also recognised as ‘clickers’ began to be widely used in lecture theatres, which would allow students to input their response to a given question in contribution to the lesson. The class would then be asked to discuss their question responses with their peers and possibly choose a different response. This is now most commonly done through online tools such as Mentimeter and Poll Everywhere. Eventually, more modern lecturers began incorporating projectors to accompany their spoken lectures, which ultimately would progress to electronic presentation tools such as PowerPoint. Additionally, the ability to record lectures and distribute presentations online meant that students could begin managing their studying schedule more effectively as they would be able to miss live lectures and watch them in their own time, in order to prioritise other elements of their studies and their deadlines.

Considering the Redundancy of the Lecture Theatre

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the structure and process of the lecture was beginning to evolve and change. With the ability to now record and distribute lectures online, lecture attendance had started to decrease, leaving lecturers and course leaders frustrated with the almost empty theatre spaces. Essentially, lectures were already accessible remotely long before social distancing measures had been first enforced, which meant that this concept was then only reinforced by the restrictions of the pandemic. In 2013, Times Higher Education reported that over 700 studies had deemed in-person lectures to be an ultimately ineffective teaching method, with very little evidence pointing to them as the primary teaching approach for learning and developing graduate career skills. They are a passive form of teaching, with students usually only listening and taking notes. As a more desirable future learning model, hybrid learning could support both on-campus participation and students working remotely. This would enable the educational system to accommodate and adapt to people’s personal needs and requirements.

But would we miss the performative and collective experience of being in a lecture?

Written by Loren Taylor in 2021. Edited by Hiral Patel